Go meteor hunting tonight on the SLOOH telescope (if you can’t get outside to view this first hand):

General information about Quadrantids

The first major shower of 2012 is the Quadrantids meteor shower. This annual shower has one of the highest predicted hourly rates of all the major showers, and is comparable to the two of the most lively, the August Perseids and the December Geminids. This celestial event is active from December 28th through January 12th and peaks on the morning of January 4th. In relation to meteor showers, the peak is defined as the moment of maximum activity when the most meteors can be seen by the observer.

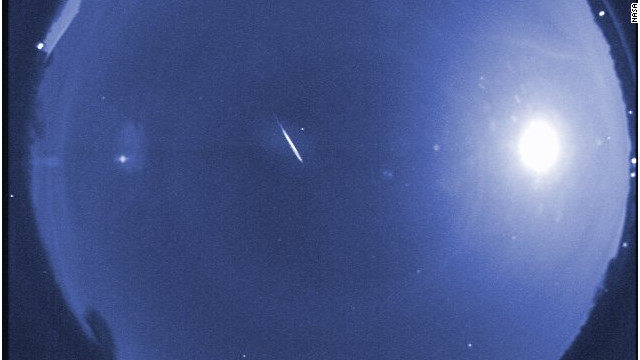

While the plus side of this annual shower is its ability to produce fireballs, and its high hourly rates, the downside is its short peak. Quadrantids has an extremely narrow peak, occurring over just a few short hours. The Quadrantids are also well known for producing fireballs, meteors that are exceptionally bright. These meteors can also, at times, generate persistent trails (also identified as trains).

Those living in the northern hemisphere have an opportunity to experience a much better view of the Quadrantids, as the constellation Boötes never makes it above the horizon in the southern hemisphere. This is great for those living in North America, much of Europe, and the majority of Asia.

Unfortunately, those of you living in Australia and lower portions of South America will have a difficult time observing the Quadrantids. Observers in higher latitudes will have better gazing conditions, but nevertheless will need to be wary of cloud cover, as conditions are typically cloudy during this time of year.

The Quadrantids in 2012

This year, the large and bright waning gibbous Moon (72% full) will coincide with the peak of the Quadrantids meteor shower. This is a stark contrast to the Quadrantids of last year, which occurred during a moonless night. While the light of the moon may reduce the quantity of meteors you’ll be able to see, you should still be able to observe all but the faintest meteors. While thus year will not be ideal for watching this January event, those willing to patiently wait it out in the cold (or warmth, for those in warmer environments) will be treated to the very first major meteor shower of 2012.

This year, the large and bright waning gibbous Moon (72% full) will coincide with the peak of the Quadrantids meteor shower. This is a stark contrast to the Quadrantids of last year, which occurred during a moonless night. While the light of the moon may reduce the quantity of meteors you’ll be able to see, you should still be able to observe all but the faintest meteors. While thus year will not be ideal for watching this January event, those willing to patiently wait it out in the cold (or warmth, for those in warmer environments) will be treated to the very first major meteor shower of 2012.

The radiant of a meteor shower is the point in the sky from where the meteors appear to come (or radiate) from. In the case of Quadrantids, its radiant lies within the now extinct constellation Quadrans Muralis. Unlike all the other major annual showers, this one is named after a constellation which longer exists. For example, the Perseids meteor shower, occurring in August, is named after the constellation Perseus. The Geminids meteor shower, occurring in December, is named after the constellation Gemini.

The constellation Quadrands Muralis was made up of a faint group of stars between the top of Boötes and the handle of the Big Dipper. Quadrands Muralis is now part of the constellation Boötes, thus making Boötes the radiant of the Quadnrantids meteor shower. To find the location of the radiant, we recommend you first find Polaris (a middling-bright star, also known as the North Star) and observe in close proximity to that area. For more specificity, it lies between the end of the handle of the Big Dipper and the four-sided figure of stars marking the head of the constellation Draco.

Particles from a minor planet, potentially hundreds to see

While this wintery spectacle appears to radiate from a constellation, they are actually caused by the Earth passing through the dust particles of the minor planet 2003 EH1. Every January, Earth passes into a trail of dust left by this minor planet, and as a result, all the dust and debris burning up in our atmosphere, produces the spectacle known as the Quadrantids meteor shower, or what are popularly recognized as “shooting stars”.

There’s no danger to sky watchers, though. The fragile grains disintegrate long before they reach the ground. While the meteors are certainly bright, they are typically not much larger than a grain of sand. However, as they travel at immense speeds, these tiny particles put on an exciting show.

During the 4th of January, shower rates will be a portion of what they could be due to the radiant lying low in the northwestern sky. On average, and under clear skies, observers should see 40 to 70 meteors per hour. However, every so often, these rates can exceed up to 90 meteors per hour in dark-sky locations. In ideal condition—no cloud cover, precipitation, city lights, and no moonlight, the Quadrantids meteor shower should host a spectacular viewing experience!

How do I know the sky is dark enough to see meteors?

If you happen to live near a brightly lit city, if possible, we recommend that you drive away from the glow of city light. After you’ve escaped the glow of the city, find a dark, safe, and possibly isolated spot where oncoming vehicle headlights will not occasionally ruin your sensitive night vision.

Look for state or city parks or other safe, dark sites. Once you have settled down at your observation spot, face toward the northeastern portion of the heavens. This way you can have the Quadrantid’s radiant within your field of view. If you can see each star of the Little Dipper, your eyes have “dark adapted,” and your chosen site is probably dark enough. Under these conditions, you will see plenty of meteors.

For many meteor showers it is often recommended to look straight up, but for this year’s Quadrantids we advise that observers face as low as possible toward the horizon without being looking at the ground. In other words, have the bottom of your field of view on the horizon. While you can still catch meteors while looking straight up, you will have an improved opportunity to observe more by looking toward the horizon. Meteors will grab your attention as they streak by!